Seeing DILI before it happens

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) remains one of the most persistent causes of clinical trial failure and post-marketing withdrawal, and one of the hardest problems in safety pharmacology. Traditional preclinical assays capture general hepatotoxicity, but they often miss subtle, heterogeneous responses, especially at clinically relevant concentrations.

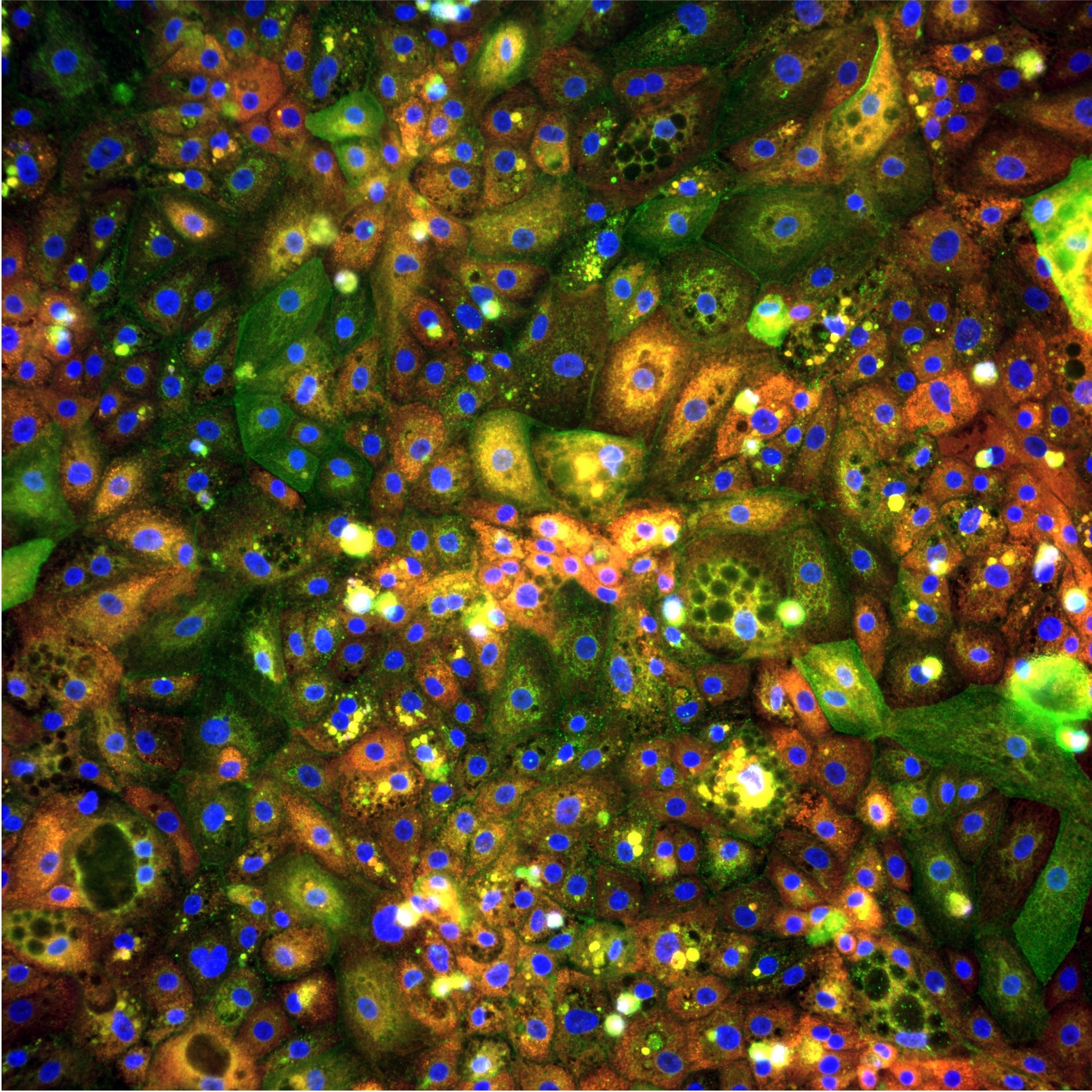

At pixlbio, we are building a data and model foundation that makes these early, sublethal effects measurable. Our platform combines our iPSC-derived hepatocytes (pixHep), phenomics at scale performed in our in-house automated Cell Painting platform, and state-of-the-art computer vision to quantify early-stage signals from toxicity-linked phenotypes at both whole-image and single-cell resolution.

This post summarizes the work we presented at this year’s Cytodata meeting in Berlin: how we generated the data, how we process it using foundation models and custom segmentation, and what the emerging DILI landscape looks like when viewed through the lens of single-cell morphology. In essence, what we presented at Cytodata was a snapshot of a growing data foundation for predictive biology, mechanistic insights, safety and toxicology.

Why iPSC-derived hepatocytes + Cell Painting?

Primary human hepatocytes are still the reference model for liver toxicity, but they are limited by availability, variability and culture stability. Immortalized liver lines remain workhorses in discovery, but they lack the metabolic and structural fidelity needed for subtle toxicity profiling.

iPSC-derived hepatocytes (pixHep) provide a renewable, human-relevant system that can be standardized across campaigns. However, to fully exploit their potential, we need readouts that go beyond a single viability endpoint. Phenomics by Cell Painting offers exactly that: multiplexed staining of cellular compartments followed by high-content imaging. Rather than pre-defining a small number of biomarkers, we capture rich morphological signatures that encode organelle damage, stress responses and changes in cell state. In our DILI study, we used Cell Painting on pixHep cultures to build a high-dimensional representation of how hepatocytes respond to a diverse panel of compounds.

Data generation: a focused DILI compound panel

To stress-test the platform and to probe early toxicity signals, we assembled a panel of 24 compounds with known or suspected DILI liability. A mix of high-risk (11), low-risk (5) and non-hepatotoxic compounds (1), as well as several agents with ambiguous (7) or context-dependent DILI signals. pixHep cultures were treated across four or eight concentrations up to 250µM, and after 48 hours, we measured Cell viability (ATP content) as a conventional endpoint and acquired Cell Painting images as multidimensional readout using our automated platform.

This design allowed us to ask a simple but critical question: when viability looks unremarkable, do the cells already show morphological fingerprints of future toxicity?

And the answer is yes, our morphological analysis clearly indicates that cells undergo morphological changes at sub-lethal doses, before the simple single endpoint viability assay could detect any viability loss.

From raw images to structured features: whole-image embeddings

A core part of our workflow is using vision foundation models to create dense representations of cellular images. Scaling phenotypic predictive toxicology requires a robust, automated way to turn terabytes of images into model-ready features. Our first layer of representation operates at the field-of-view level.

We use a vision foundation model (DINOv3) to compute dense embeddings directly from raw images of each fields of view without requiring segmentation. These embeddings capture global morphology, that is: cell density, texture, and organelle organization among others, without manual feature engineering.

This step delivers:

- Compact representations for rapid visualization (e.g. UMAP) and clustering of treatments

- A standardized feature space that can be reused across campaigns

Whole-image embeddings already reveal structure: compounds with similar mechanisms cluster together, and high-toxicity conditions separate cleanly from DMSO controls. But they still average over heterogeneous single-cell responses.

Going deeper: single-cell segmentation and morphology

DILI is often a story of subpopulations: a subset of hepatocytes undergoes stress or death, while others appear relatively unaffected. To capture this heterogeneity, we move to single-cell resolution.

pixHep images pose specific challenges: variable cell size, diffuse boundaries and tightly packed clusters. Off-the-shelf segmentation struggles in this complex task, so we trained a custom Cellpose–SAM based model tailored to pixHep morphology.

This pipeline:

- Uses a foundation-model prior to proposing object boundaries, even when edges are weak.

- Refines segmentation to separate overlapping cells and nuclei.

- Associates per-cell masks with both classical morphological metrics (size, shape, intensity, texture) and dense DINOv3 embeddings computed at pixel level.

The result is a high-dimensional single-cell feature table in which each hepatocyte is represented by hundreds of descriptors summarizing its structural and organelle state.

Modelling heterogeneity: from cells to subpopulations

With single cell features in place, we can move beyond mean responses and start reasoning about cellular subpopulations.

Our analysis focuses on three aspects:

- Heterogeneity profiles

For each treatment–concentration pair, we examine how cells distribute across the morphological space. Toxic compounds often increase variance: some cells exhibit pronounced mitochondrial swelling, others show nucleolar stress or cytoplasmic condensation.

- Subpopulation discovery

Using unsupervised clustering on single-cell embeddings, we identify recurrent morphological states that recur across compounds, for example, a swollen mitochondria + fragmented nuclei state, or a compact cytoplasm + reduced nucleolar signal state. These states can be tracked as a function of dose and time.

- Early mechanistic toxicity signals

Importantly, we can resolve treatment-induced morphological changes at doses where ATP levels and bulk viability remain unchanged, indicating that single-cell morphology is a more sensitive readout than standard viability assays. Many of these early phenotypes map onto known DILI-related processes, including lipid accumulation, ER stress, and mitochondrial damage.

For example, for the cholestatic drug Chlorpromazine, we observe cytoskeletal disruption at doses more than ten-fold lower than those that affect cell viability, suggesting an early disruption of bile canalicular function. By linking such morphological states to specific DILI-relevant mechanisms, we can infer what processes are being engaged in the cell well before overt loss of viability is detectable.

What the DILI landscape looks like

When we embed all single cells across compounds into a common low-dimensional space, a striking picture emerges:

- Distinct “islands” of morphology correspond to different mechanisms of injury (e.g. mitochondrial impairment, oxidative stress, ER stress).

- High-risk DILI compounds tend to occupy extreme regions of this space, with large fractions of cells in stressed states.

- Low-risk or non-hepatotoxic compounds cluster closer to DMSO, with only modest shifts in a minority of cells.

- Compounds with ambiguous clinical DILI profiles show intermediate patterns—often with specific subpopulations adopting high-risk morphologies despite minimal global viability loss.

These patterns suggest that single-cell phenomics can disentangle subtle safety signals long before traditional endpoints become abnormal.

Lessons From Cytodata

Presenting this work at Cytodata was an opportunity to stress-test our approach with a community that lives and breathes image-based profiling.

Several themes came out of the discussions:

- Standardization matters. Using iPSC-derived hepatocytes and a reproducible Cell Painting protocol makes it feasible to compare DILI signatures across campaigns and, ultimately, across labs.

- Foundation models are becoming the default. Both for segmentation and feature extraction, there was broad agreement that model reuse (DiNO, SAM, Cellpose variants) is key to scaling phenotypic screens. Our experience with pixHep reinforces this: investing early in a robust vision backbone pays dividends across projects.

- Single-cell resolution is no longer optional. Many groups highlighted the importance of heterogeneity for toxicity, resistance and cell-state shifts. The ability to move seamlessly from plate-level QC to single-cell subpopulations resonated strongly.

For us, Cytodata validated that the infrastructure we have built at pixlbio based on our phenomics platform (automated Cell Painting, automated image acquisition, foundation-model pipelines, and scalable single-cell analytics), is aligned with where the field is going.

Where we are heading next

The DILI study is just the starting point. Building on this work, we are:

- Expanding the compound panel and integrating external reference sets to benchmark against existing DILI predictors.

- Linking morphological subpopulations to orthogonal readouts (transcriptomics, secreted biomarkers) to better understand mechanisms.

- Refining dose-response models to prioritize clinically actionable concentration ranges.

- Generalizing the pipeline beyond hepatocytes to other iPSC-derived cell types relevant for safety pharmacology.

Conclusion

AI-Powered Cell Painting in iPSC-Derived Hepatocytes for Liver Toxicity Profiling

- Bray MA, Singh S, Han H, Davis CT, Borgeson B, Hartland C, Kost-Alimova M, Gustafsdottir SM, Gibson CC, Carpenter AE. Cell Painting, a high-content image-based assay for morphological profiling using multiplexed fluorescent dyes. Nature protocols. 2016 Sep;11(9):1757-74.

- Siméoni O, Vo HV, Seitzer M, Baldassarre F, Oquab M, Jose C, Khalidov V, Szafraniec M, Yi S, Ramamonjisoa M, Massa F. Dinov3. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.10104. 2025 Aug 13.

- Stringer C, Wang T, Michaelos M, Pachitariu M. Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nature methods. 2021 Jan;18